The Sessions: Human in All Its Complexity

by Lawrence Carter-Long

Tell almost anyone you’re going to see a movie that has something to do with disability and odds are you’ll collide with a whole host of expectations. Disability as traditionally portrayed on film would lead one to expect you were off to see an inspiring yarn about overcoming adversity or perhaps a tragic tale of potential denied by the cruel hand of fate. If that film is released in October odds are you’d be off to see a horror film complete with a disfigured villain hell bent on exacting revenge on a world that has done them wrong.

You probably wouldn’t expect to see a relationship movie and a relationship movie with sex at its core wouldn’t be a likely option.

Until now. With “The Sessions” writer/producer/director Ben Lewin effectively plays against type skillfully sidestepping expectations about what a relationship movie involving disability could be to deliver an often funny, refreshingly subtle chapter in the life of poet Mark O’Brien, a disabled man who hires a sex surrogate in the quest to lose his virginity at the age of 38. The fact “The Sessions” somehow never becomes mawkish or flip about either the films surprising subject matter or its engaging human subjects is perhaps even more remarkable.

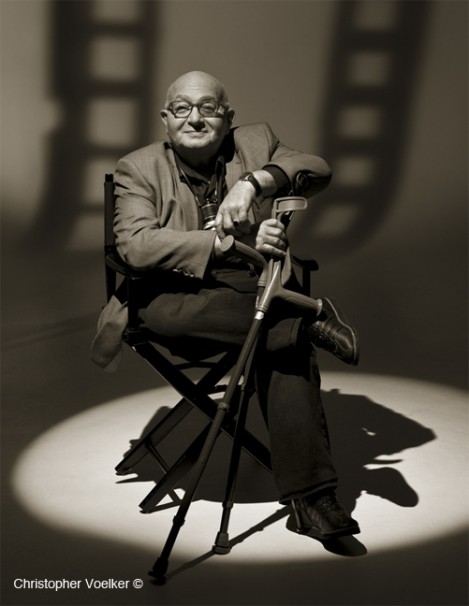

Lewin, whose TV credits include “Touched by an Angel,” is a polio survivor himself and his experiences living with the condition clearly helped inform “The Sessions” in important ways. At the screening I attended, which was accompanied with a Q&A by Lewin, his wife who also produced and lead actor John Hawkes, Lewin revealed that he never set out to make a biopic about O’Brien. It was while surfing the internet trawling for “tasteless material” about sex and disability for an sitcom idea called “The Gimp” that Lewin found O’Brien’s 1990 story “On Seeing a Sex Surrogate” which served as a template for the film.

Winter Bone’s John Hawkes plays Mark O’Brien as a disabled everyman, our own sexually inexperienced but earnestly inquisitive Jimmy Stewart. He isn’t a Brando-esque hunk, exuding righteous anger as Daniel Day-Lewis’ did in “My Left Foot” – a groundbreaking performance oddly becoming its own disability stereotype two decades later – no, by channeling O’Brien’s sense of irreverence, a quality clearly shared by Lewin, that keeps “The Sessions” from swimming into melodrama and serves as a buoy for the current of dramatic tension that a less skilled cast, and less informed director could easily overplay.

Lewin navigates the often treacherous waters between comedy and a drama with a light touch, never emphasizing one at the expense of the other or letting audiences forget that much like O’Brien and Helen Hunt’s understated, moving portrayal of his sexual surrogate, Cheryl. Both the subject matter and the manner in which it is presented is almost matter-of-fact, never gratuitous. It is easy to imagine how these scenes could have come off as too intimate or voyeuristic. Lewin gets around this problem by instead of showing O’Brien actually having sex, he invented the character of Father Brendan, the priest Mark confides to played by William H. Macy.

It is to Father Brendan that Mark recounts his escapades in sometimes excruciating, hilarious detail. “The most explicit stuff didn’t happen on the screen—it happened in the confessional—and that automatically made it funny,” said Mr. Lewin. Thoughtful, wry and often hilarious, Macy doesn’t resort to broad comedy, his performance is conflicted and at times perplexed, but always good hearted and good humored. A performance reminiscent of vintage Spencer Tracy, an affable but patient priest who never comes right out in support of or to dismiss O’Brien’s desires, but nevertheless seems to always have a sparkle in his eye signaling understanding – minus shame or titillation – that expresses a solidarity beyond words. O’Brien knows it, and the audience does too.

In fact, these relationships – romantic and otherwise — are the heart and soul of “The Sessions.” From the beginning when Mark shows concern over firing an inept employee – but does it anyway, because well, she’s inept — to his banter with Macy, the dedication shown by his attendants, the frightened phone call for help he makes when the power goes out literally threatening his life, to the disabled friend who opens her apartment – specifically her bedroom – for his sessions with Hunt’s Cheryl there is a interwoven feel to all the relationships in “The Sessions” that seem as specific and unique to O’Brien as they seem natural to those watching.

Mark O’Brien once wrote: “The two mythologies about disabled people break down to one: we can’t do anything, or two: we can do everything. But the truth is, we’re just human.”

As the credits roll the lasting impression left by “The Sessions” is one of community, of connection, of humanity. By not denying the person or the disability out of a sense of misplaced sense of political correctness but rather allowing both, in all their complexities to simply be, the film transcends both expectations and convention.

By allowing O’Brien to be “just human” as he was without imposing anything more “The Sessions” provides the space for audience members to consider the possibility that “just human” encompasses more than they’ve ever imagined, more than they’ve been led to believe.

Lawrence Carter-Long is curator/co-host of “The Projected Image: A History of Disability in Film” presented Tuesdays in October 2012, on Turner Classic Movies in partnership with Inclusion in the Arts.